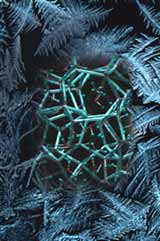

Cool ice simulation

Cracking ice took six years and a supercomputer. <br>© Nature <br>

Computers finally catch up with freezing water.

Beneath the familiar business of water freezing to ice lies a process so complex it has taken Japanese researchers six years to make the first realistic computer simulation of it1.

Iwao Ohmine and his colleagues at Nagoya University pinned down water’s capricious path from liquid to solid using a supercomputer. They calculated changes in the relative orientation of water molecules from the forces acting between them. After many such calculations on 512 water molecules and „a long, long wait“, they finally spotted one freezing event.

The team found that the spontaneous appearance of several unusually long-lasting hydrogen bonds between water molecules in one location is the crucial first step in forming ice. This nucleus slowly changes shape and size until more stable bonds rapidly spread throughout the system, turning the liquid to ice.

Just a phase

The process of a liquid becoming a solid is called a phase transformation. At high temperatures, thermal energy pushes individual molecules or atoms around. As the temperature falls, that energy diminishes, so the molecules or atoms move less and less.

At the freezing point, the interaction between the molecules or atoms is larger than the thermal energy. So the most stable state is solid matter, with a regular, crystalline structure.

In simple liquids such as molten metals or salts, this transformation proceeds smoothly. But in water, it is as though the molecules are lost in mountainous terrain without a map – they wander many valleys and passes before finally finding home.

The problem is that water molecules have a penchant for fleeting, orientation-dependent interactions with their neighbours. This means that liquid water can adopt many different microscopic structures separated by only small energy barriers.

Water can move between these without reaching a configuration that triggers the transformation to solid ice. This behaviour also explains ’supercooling’ – water’s propensity to remain liquid even when cooled well below its freezing point.

References

- Matsumoto, M., Saito, S. & Ohmine, I.. Molecular dynamics simulation of the ice nucleation and growth process leading to water freezing. Nature, 416, 409 – 413, (2002).

Media Contact

Alle Nachrichten aus der Kategorie: Interdisziplinäre Forschung

Aktuelle Meldungen und Entwicklungen aus fächer- und disziplinenübergreifender Forschung.

Der innovations-report bietet Ihnen hierzu interessante Berichte und Artikel, unter anderem zu den Teilbereichen: Mikrosystemforschung, Emotionsforschung, Zukunftsforschung und Stratosphärenforschung.

Neueste Beiträge

Anlagenkonzepte für die Fertigung von Bipolarplatten, MEAs und Drucktanks

Grüner Wasserstoff zählt zu den Energieträgern der Zukunft. Um ihn in großen Mengen zu erzeugen, zu speichern und wieder in elektrische Energie zu wandeln, bedarf es effizienter und skalierbarer Fertigungsprozesse…

Ausfallsichere Dehnungssensoren ohne Stromverbrauch

Um die Sicherheit von Brücken, Kränen, Pipelines, Windrädern und vielem mehr zu überwachen, werden Dehnungssensoren benötigt. Eine grundlegend neue Technologie dafür haben Wissenschaftlerinnen und Wissenschaftler aus Bochum und Paderborn entwickelt….

Dauerlastfähige Wechselrichter

… ermöglichen deutliche Leistungssteigerung elektrischer Antriebe. Überhitzende Komponenten limitieren die Leistungsfähigkeit von Antriebssträngen bei Elektrofahrzeugen erheblich. Wechselrichtern fällt dabei eine große thermische Last zu, weshalb sie unter hohem Energieaufwand aktiv…